Articles

The Clean: Don’t Just Fall Down, Turn It Over

October 9 2017

October 9 2017

A refrain of mine I’m sure plenty of people are sick of hearing by this point is that in the Olympic lifts, there is never a moment in which you’re just letting things happen; you need to always be actively making them happen. The barbell doesn’t want to be where you’re trying to put it—it wants to be resting on the floor where it started, and it’s going to do whatever it can to get back there. You have to force it to do what you want, and that requires constant action and attention.

This idea comes into play very obviously in the third pull of the lifts (moving under the bar), because lifters tend to be so overly focused on elevating the bar in the first and second pulls that they forget everything else after that. The clean is more susceptible to this problem than the snatch because the lifter and bar have to cover only about half the distance relative to each other that they do in the snatch, and in a technical sense it’s a simpler movement. In other words, you can get away with a lot more sloppiness and inactivity.

This leads to a lot of lifters relying on the launch the bar up and fall down under it method of cleaning—they get away with it enough of the time that they don’t feel an urgent need to fix anything. The problem with this approach is two-fold: the bar crashes onto the shoulders, which means more chance for instability and imbalance and far more difficulty recovering from the bottom; and the clean is inconsistent because its success is based largely on chance.

Just like in the snatch, the movement under the bar in the clean should be an active one—pull yourself down under the bar, bring the bar and the body together smoothly into the correct positions, and secure those positions aggressively.

The idea is simple: the body needs to move down toward the bar, and the bar needs to continue moving up and back toward the shoulders so that the two are in close proximity before the elbows spin around the bar. If the bar and shoulders are distant, initiating the turnover means the arms are actually curling the bar instead of being spun around it, and the speed is reduced, both increasing the likelihood of an incomplete turnover and weak rack position.

The elbows will not need to be pulled very high along this path—it’s a brief movement, and may not even be noticeable in real time, but the direction and the generation of momentum are the keys. Pulling them too high before spinning them around the bar will also slow the turnover and create crashing, and few lifters have the shoulder mobility to pull high even if that were desirable.

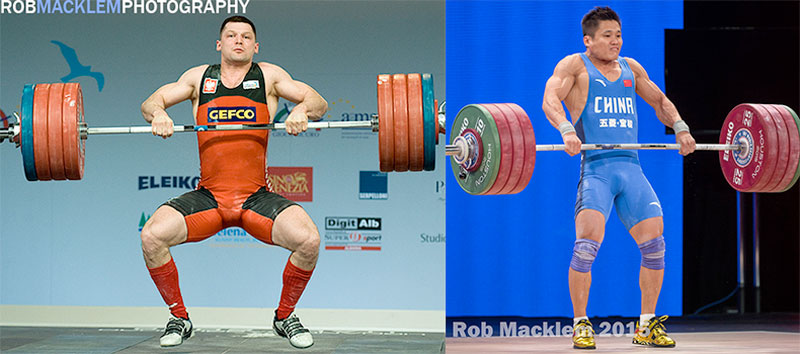

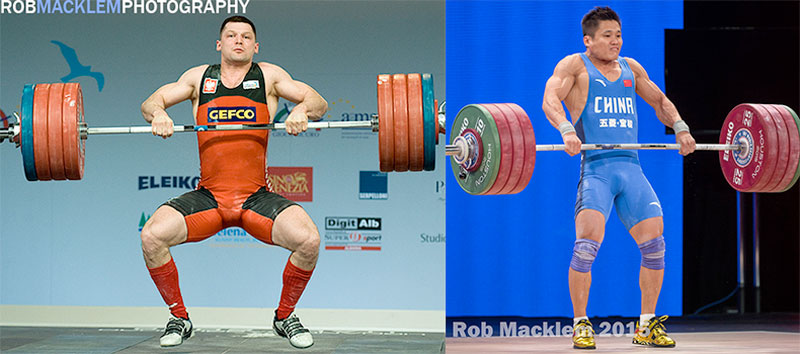

Lifters will vary in how much they elevate the elbows in this initial downward pull; for some it will be very pronounced, and for others will be a very brief motion—really just the abrupt initiation of the pull under. Reasons can range from mobility differences to a natural feel for the movement. (See photos below for examples of two world record holders—one with very pronounced elbow elevation, and the other with relatively little).

Left: Pronounced elbow elevation before turnover; Right: minimal elbow elevation before turnover. Both lifters pictured have broken world records in the clean & jerk (Szymon Kolecki and Xiaojun Lu).

This pulling motion—basically an upright row—allows you to change directions more quickly and achieve more downward speed, which means an easier turnover of the elbows and securing the bar in the rack position in a higher position from which you have more time and space to brace and absorb the impending downward force—you’re literally tugging yourself down toward the bar, and then spinning the elbows around. That greater speed downward of the body (and greater preservation of the bar’s existing upward speed) allows the bar and shoulders to continue moving to each other largely under existing momentum while the elbows spin around the bar. The turn of the elbows around the bar itself is NOT an effective way to move your body down, and it will fail entirely eventually as weights increase.

Flexing the arm at the elbow and pulling the elbows back immediately is a weaker movement, but it can work. It relies on the fact that the distance needed to be covered by the bar and body from the top of the pull into the rack position is so short and consequently pretty easy to accomplish. This alternative method needs to be equally active—it’s not inactivity, but a different action. The lifter will squeeze the shoulder blades and elbows back and keep the elbows close to their sides to maintain the bar’s proximity to the body as they pass each other—basically a reverse curl with the bar nearly sliding up the chest—then spin the elbows around into the rack position as the bar and shoulders near each other.

In any case, the crux is maintaining proximity of the bar and body and actively bringing the bar into the proper rack position while bringing the shoulders to meet it smoothly. This is what creates a rapid pull under the bar and a solid receiving position, which means an easier recovery with more weight and a lot less pounding on the body. In my opinion, which method works best is very individual and is something to be experimented with.

The second part of this active clean turnover is the receiving position itself. A great, active turnover won’t mean much if you bring yourself and the bar into a loose, poor position to absorb and control the downward force. This part is simple—you’re just trying to be in your perfect front squat position. Flat feet with balance across the whole thing, the trunk as upright as possible and still pressurized with air and clamped down forcefully, the shoulders pushed forward and slightly up, and the elbows up. We’re creating a rock-solid platform for the bar to land on, trying to prevent any movement at all, and to avoid any collapsing or shifting of the body below it.

A solid, aggressive receiving position can withstand a surprisingly large degree of bar crashing and even improper positioning in the rack, so in addition to being helpful for stronger, easier, faster recoveries from the bottom in all cleans, it’s also back-up protection against misses due to errors earlier in the lift.

Quit letting things happen and take control of your cleans.

This idea comes into play very obviously in the third pull of the lifts (moving under the bar), because lifters tend to be so overly focused on elevating the bar in the first and second pulls that they forget everything else after that. The clean is more susceptible to this problem than the snatch because the lifter and bar have to cover only about half the distance relative to each other that they do in the snatch, and in a technical sense it’s a simpler movement. In other words, you can get away with a lot more sloppiness and inactivity.

This leads to a lot of lifters relying on the launch the bar up and fall down under it method of cleaning—they get away with it enough of the time that they don’t feel an urgent need to fix anything. The problem with this approach is two-fold: the bar crashes onto the shoulders, which means more chance for instability and imbalance and far more difficulty recovering from the bottom; and the clean is inconsistent because its success is based largely on chance.

Just like in the snatch, the movement under the bar in the clean should be an active one—pull yourself down under the bar, bring the bar and the body together smoothly into the correct positions, and secure those positions aggressively.

Pulling the elbows up and out to initiate the movement down under the bar is my preferred method. This maximizes the downward acceleration, creates the momentum necessary for a quick turnover of the elbows, and encourages the bar and body to move the right way to achieve a solid receiving position.the movement under the bar in the clean should be an active one

The idea is simple: the body needs to move down toward the bar, and the bar needs to continue moving up and back toward the shoulders so that the two are in close proximity before the elbows spin around the bar. If the bar and shoulders are distant, initiating the turnover means the arms are actually curling the bar instead of being spun around it, and the speed is reduced, both increasing the likelihood of an incomplete turnover and weak rack position.

The elbows will not need to be pulled very high along this path—it’s a brief movement, and may not even be noticeable in real time, but the direction and the generation of momentum are the keys. Pulling them too high before spinning them around the bar will also slow the turnover and create crashing, and few lifters have the shoulder mobility to pull high even if that were desirable.

Lifters will vary in how much they elevate the elbows in this initial downward pull; for some it will be very pronounced, and for others will be a very brief motion—really just the abrupt initiation of the pull under. Reasons can range from mobility differences to a natural feel for the movement. (See photos below for examples of two world record holders—one with very pronounced elbow elevation, and the other with relatively little).

Left: Pronounced elbow elevation before turnover; Right: minimal elbow elevation before turnover. Both lifters pictured have broken world records in the clean & jerk (Szymon Kolecki and Xiaojun Lu).

This pulling motion—basically an upright row—allows you to change directions more quickly and achieve more downward speed, which means an easier turnover of the elbows and securing the bar in the rack position in a higher position from which you have more time and space to brace and absorb the impending downward force—you’re literally tugging yourself down toward the bar, and then spinning the elbows around. That greater speed downward of the body (and greater preservation of the bar’s existing upward speed) allows the bar and shoulders to continue moving to each other largely under existing momentum while the elbows spin around the bar. The turn of the elbows around the bar itself is NOT an effective way to move your body down, and it will fail entirely eventually as weights increase.

Flexing the arm at the elbow and pulling the elbows back immediately is a weaker movement, but it can work. It relies on the fact that the distance needed to be covered by the bar and body from the top of the pull into the rack position is so short and consequently pretty easy to accomplish. This alternative method needs to be equally active—it’s not inactivity, but a different action. The lifter will squeeze the shoulder blades and elbows back and keep the elbows close to their sides to maintain the bar’s proximity to the body as they pass each other—basically a reverse curl with the bar nearly sliding up the chest—then spin the elbows around into the rack position as the bar and shoulders near each other.

In any case, the crux is maintaining proximity of the bar and body and actively bringing the bar into the proper rack position while bringing the shoulders to meet it smoothly. This is what creates a rapid pull under the bar and a solid receiving position, which means an easier recovery with more weight and a lot less pounding on the body. In my opinion, which method works best is very individual and is something to be experimented with.

The second part of this active clean turnover is the receiving position itself. A great, active turnover won’t mean much if you bring yourself and the bar into a loose, poor position to absorb and control the downward force. This part is simple—you’re just trying to be in your perfect front squat position. Flat feet with balance across the whole thing, the trunk as upright as possible and still pressurized with air and clamped down forcefully, the shoulders pushed forward and slightly up, and the elbows up. We’re creating a rock-solid platform for the bar to land on, trying to prevent any movement at all, and to avoid any collapsing or shifting of the body below it.

A solid, aggressive receiving position can withstand a surprisingly large degree of bar crashing and even improper positioning in the rack, so in addition to being helpful for stronger, easier, faster recoveries from the bottom in all cleans, it’s also back-up protection against misses due to errors earlier in the lift.

Quit letting things happen and take control of your cleans.